“A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.” – MLK, “Beyond Vietnam,” 1967

A few weeks ago, Boston Latin School students attended the annual schoolwide Martin Luther King Jr. celebration. Amidst inspiring performances and speeches, students heard this year’s theme over and over again: “Building the Beloved Community — It Starts with Me.” This theme, selected from the King Center, was MLK’s ultimate vision for the world: a place where the “triple evils” in society — poverty, racism and militarism — had been defeated, and equality and love formed the basis of society.

This vision, however, has been whitewashed by American society, resulting in the message becoming a vague call for “equality” and “brotherhood,” without explaining how to get there. Dr. King is often reduced to the ideals of nonviolence and peace, stripped of the context he used them for, which was the struggle against racism, capitalism and militarism.

Oriana Dunker (II) describes this phenomenon, saying, “Nowadays, in schools, rather than his message being for civil rights, for Black liberation and celebration, it’s become ‘he is peace’ […] like how Gandhi is thought of as ‘nonviolence’ and not everything he did in India.” Dr. King must be remembered for all of his goals — for peace, but also for the breaking down of oppressive systems that blocked such peace.

“Loose and easy language about equality, resonant resolutions about brotherhood fall pleasantly on the ear, but for the Negro there is a credibility gap he cannot overlook. He remembers that with each modest advance the white population promptly raises the argument that the Negro has come far enough.” – MLK, Where Do We Go From Here, 1967

Dr. King’s name is often invoked by politicians who are deploring various protests or equity movements, claiming they “contradict MLK’s values” in an attempt to suppress them. For example, Biden told Black Lives Matter protestors who looted stores that it “was not what MLK wanted” and therefore they should stop.

Although MLK believed peaceful protest was much more effective than looting, he sympathized with looters. In “The Role of the Behavioral Scientist in the Civil Rights Movement,” he says that “[looters,] most of all, [feel] alienated from society and knowing that this society cherishes property above people, he is shocking it by abusing property rights. […] Let us say boldly that if the violations of law by the white man in the slums over the years were calculated and compared with the law-breaking of a few days of riots, the hardened criminal would be the white man.”

Fox Business anchor David Asman says, “Now it sounds to me like you took a page out of Dr. King’s book about judging by the content of character rather than skin color,” in response to Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt banning Diversity, Equity and Inclusion programs. Politicians who invoke Dr. King’s name in this way are misrepresenting his views, and just using his name to justify their policies as progressive. By teaching a more holistic view of MLK, BLS can work past this single ideology that Dr. King is too often tied to.

“The evils of capitalism are as real as the evils of militarism and racism. The problems of racial injustice and economic injustice cannot be solved without a radical redistribution of political and economic power.” – MLK to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1967

On MLK Day, most BLS students are not learning enough about Dr. King’s more complex ideas. Students can handle more than the “I Have a Dream” speech, and deserve more than that, especially at a time when the question of how to protest more effectively is at the forefront of many minds.

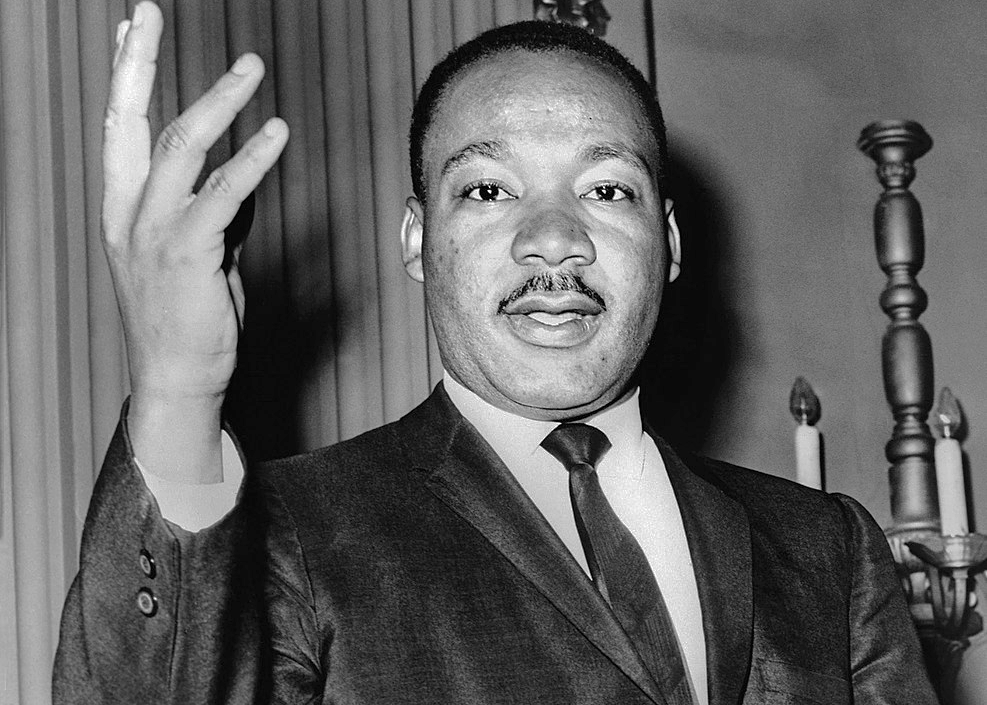

Ms. Cheralyn Pinchem, BLS history teacher and Black Leaders Aspiring for Change and Knowledge (BLS B.L.A.C.K.) faculty advisor says, “As educators, if we’re going to continue to do school wide celebrations and acknowledge this day, we need to do more than the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. More than just Dr. King looking out upon the crowd with his hand up in the air in an idealistic way. […] If you take ‘I Have a Dream,’ plus what he said to the sanitation workers, plus his letter from a Birmingham Jail, plus his speaking out against Vietnam, then you get the whole arc of who he is.” It’s not about telling kids what to think, but instead giving them access to the whole truth and letting them form their own opinions.

Education like this requires more than one two-hour block, and to do this MLK day at BLS should become a fully mandated day split into three rotating parts: celebration, service and education.

The assembly would remain a showcase of BLS talent, highlighting African American, Afro-Cuban and African cultures in particular. Excerpts from MLK’s speeches like “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” could be added, but overall it should remain similar to the current programming.

Then, in the second third, students would participate in community service activities, perhaps building care packages for organizations such as Rosie’s Place, or writing letters to representatives after hearing an American Civil Liberties Union presentation.

The middle third of the day would be a time of learning and reflection. The school could invite speakers, teachers and students to give presentations about MLK’s life or beliefs. Then, students could engage in tough conversations about topics like race, class, military and government in hopes of finding common ground, gaining understanding and growing closer to one another.

“Whites, it must frankly be said, are not putting in a similar mass effort to reeducate themselves out of their racial ignorance. It is an aspect of their sense of superiority that the white people of America believe they have so little to learn.” – MLK, Where Do We Go From Here, 1967

All of these additions would take a huge amount of effort and investment, and would require participation from more BLS teachers. Ms. Pinchem says, “Having more teachers at the table to decide what that day looks like rather than just a handful of teachers is something I’d like to see changed. I’m exhausted, because we were doing things all over, but then I’m walking past classrooms that are not doing anything. And I’m like, ‘why is that?’ Some people are very content and comfortable with wearing a pin, taking their kids to the auditorium and saying, ‘I celebrated Dr. King’ […] if everyone felt it was their responsibility, we’d start to see that beloved community.”

As Ms. Pinchem explains, certain teachers at the school do not feel that educating students on Dr. King is important. Whether out of a fear of being “politically incorrect” or a perceived loss of class time, they fail to recognize the educational value that a whole day dedicated to him would have on our community. Students would be forced out of their isolated social groups and made to think critically about the important issues facing our world. This would make many students feel like what they learn in school is more applicable to their daily life.

Most teachers already do not assign work on this day, since it would leave some of their other classes behind. Finally, most students at BLS do not encounter Black history outside of discussions of slavery as they do not take classes such as African American Studies. It’s crucial to learn about the wide scope of Black history to truly understand our country and progress forward.

“If peace means a willingness to be exploited economically, dominated politically, humiliated and segregated, I don’t want peace. In a passive non-violent manner we must revolt against this peace.” – MLK, “When Peace Becomes Obnoxious,” 1956

Outside of MLK day, there’s much more work to do to further liberation efforts. It starts by listening and educating ourselves. Instead of shying away from tough conversations about race, fearing we might “make a mistake,” we should engage with these issues and risk embarrassing ourselves.

Ita Berg (II), a white member of BLS B.L.A.C.K., shares her advice for allies to Black liberation movements. She says, “Don’t worry about sounding weird; you probably will. [But] you have to listen. I think a lot of times people who really do mean well kind of take over movements that are really for Black liberation and social justice. […] If something is not affecting your life, it’s not hurting you everyday, then you have to participate in the movement from a background perspective.”

Educating, listening and taking a background role are all important for allies to make everyone in the BLS community feel heard. It is a privilege to be able to opt in and out of learning about the struggles of another group, because for others, it’s their lived reality.

Dunker reflects on this, sharing, “If we’re talking MLK, civil rights, segregation — those are my grandparents. If we’re looking at Black Lives Matter protests and rioters on the screen of our zoom, and talking about the start of the Metco program? Well, you write a paragraph about that, submit it, and it’s done. I do that, and then I go home and that’s my life.” Allies must try to listen and learn, so that the responsibility of educating and reforming doesn’t all fall on those facing oppression by the system.

One great way to do this is by attending the Topol Fellows’ Black Film Club movie screenings that are happening every Friday in February. These films highlight a range of topics related to uplifting Black voices.

Take action. Listen. Read. Make mistakes. Work to make the Beloved Community a reality.

“The end is reconciliation; the end is redemption; the end is the creation of the Beloved Community. It is this type of spirit and this type of love that can transform opponents into friends. It is this type of understanding goodwill that will transform the deep gloom of the old age into the exuberant gladness of the new age. It is this love which will bring about miracles in the hearts of men.” – MLK, “Facing the Challenge of a New Age,” 1956