Food Biases Need To-Go

With American dieting culture as prominent as ever, one must question and eliminate the prejudices and exclusion of cultural cuisines from a mainstream “healthy” diet. After decades of American nourishment shifting towards processed and junk foods, a nutritious revolution has sparked and largely impacted the diets and mindsets of many.

In simple terms, American dieting culture can be summarized in a few words along the lines of “green,” “fresh” or “clean.” The foods at the forefront of this culture are salads, smoothies and other low-calorie or low-carb foods. American dieting culture is marketed for a mainly white society, a fact shown in its discrimination against other ethnic cuisines.

Many believe ethnic foods to be unhealthy and label them with words like “filling,” “greasy” or even “dirty.” Some also tend to perpetuate the stereotype that they are bad for digestion or full of additives. For example, how often have you heard that Mexican food would give you diarrhea or that the monosodium glutamate (MSG) in Chinese food would lead to high blood pressure?

Such labels indicate an intersection between racism and food. Italian, French and other European cuisines are regarded as “refined” and appear in mainly dine-in restaurants. Meanwhile, the cuisine of other cultures is seen as “cheap” or “low-quality” and fit for only takeout. This large disparity demonstrates the racism embedded deep within American dieting culture.

The exclusion of ethnic foods from the American diet is puzzling, as they are often healthier. Traditional American foods include excessive amounts of red meat, starch and processed ingredients. Despite other cuisines being statistically and empirically healthier, the stigma continues to persist.

A prime example is MSG. It is often regarded as dangerous when used in Chinese food, but not when it is found in Chick-fil-A’s Deluxe Chicken Sandwich. In fact, over-consumption of the seasoning supposedly can induce “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.” It is not difficult to observe the blatant sinophobia that has impacted public perception of food.

Ethnic foods are not as unhealthy as they seem, but still, America has adopted aspects of certain cuisines and made them more “suitable” for the palate of predominantly white society.

For instance, the adaptation of Japanese cuisine has become quite prominent. Mochi traditionally consists of chewy rice balls filled with bean paste. American brands popularize, however, mochi balls filled with ice cream or made into doughnuts. A similar effect has occurred with ramen, which has been transformed from a rich noodle soup into a dehydrated package of instant starch in the American public eye.

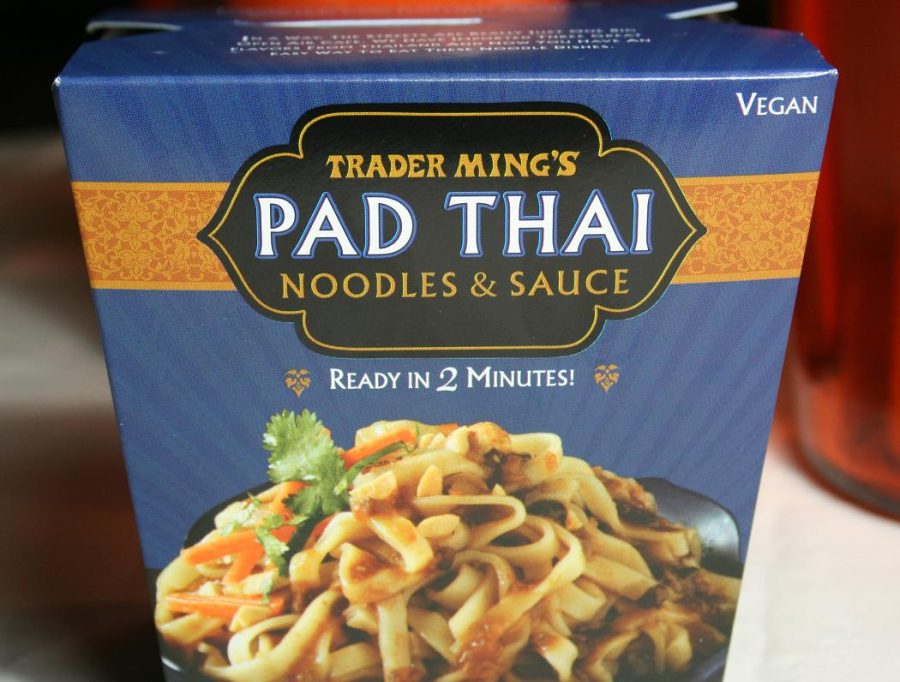

In contrast, sometimes the American adaptation of certain aspects of cultural cuisines markets them as supposedly healthier. Even when ethnic food is healthy in the first place, it might be repackaged in a nonthreatening, “Americanized” way to appeal to consumers.

This reclaiming of elements is extremely controversial as it seemsto alter or repurpose ethnic foods, thereby disrespecting their origins. For example, turmeric has been used as a medicinal spice in South Asia for thousands of years. American dieting culture, however, has reformatted and repurposed it into pills and face masks.

Faria Zaman (II), co-president of Boston Latin School Desi Society, a club dedicated to connecting students of the South Asian culture, says, “No one is trying to ‘gatekeep’ foods or spices or anything like that. It is just the ignorance and lack of awareness of where these things originated and what they were originally used for. That’s what people here don’t know about.”

The same effect occurs with kombucha and coconut milk. Kombucha, originating from China, has been popularized in American supermarkets like Whole Foods. In terms of coconut milk, when used in curry or stew, it is considered fattening. When it is mixed into Starbucks drink, however, its negative connotation is forgotten.

Jasmine Lee (I), co-president of theBLS Food Club, illustrates that “[American manufacturers] often disregard the culture and create a dish entirely tailored to the ‘American’ diet and label it as ‘authentic.’”

While one might argue that adaptation indicates a step towards embracing other cuisines, it is misleading. American diet culture cherry-picks certain ethnic foods and claims to improve them. This intersection of food and racism blatantly requires more attention from the society it impacts.

Ms. Leah Lipschitz, a BLS health teacher, says, “Food, yes it is a building block for our health, but it is a way that people connect. It is a way that communities gather, and there is no one way to do it.”