More than Just Streetcar Art

When you come across graffiti, what do you think of? To you, is it art, destruction, a territorial marking or something else? Often, we fail to recognize the impact and history of the art in our surroundings. A new exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) works to enlighten viewers about the art in their daily lives and its influence, specifically graffiti.

“Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation” runs from October 18, 2020 to May 16, 2021 in the Ann and Grant Gunn Gallery. The exhibit includes the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat, A-One, ERO and others. It is one of the first exhibits to showcase the impact of the post-graffiti and neo-expressionist movement on hip-hop culture.

During the 1970s, Basquiat was a prominent street artist in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Most of his work was signed “SAMO,” which was an informal graffiti duo composed of him and Al Diez, another street artist. It did not take long for the images sprayed on subway cars to move to canvases displayed in art galleries.

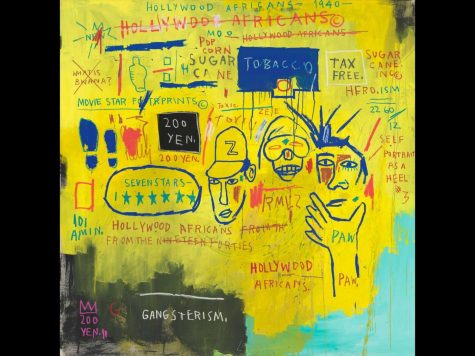

In the 1979 documentary Graffiti/Post Graffiti, Paul Tschinkel, who is a founder and executive producer, states, “Basquiat makes fresh childlike paintings that combine Afro-American and European-American culture.” Hollywood Africans, painted by Basquiat, Toxic and Rammellzee, references the African American experience in the traditionally White American Hollywood. Words like “tobacco” and “gangsterism” are written to signify the diminishment of African American artists within pop culture. Comparing the oppressed to the oppressor, and how the oppressed can emerge into the world of the oppressor, is a common theme of Basquiat’s works.

Billy Dean Thomas, a hip-hop recording artist and creative consultant, states that “This whole exhibition […] is about dreaming and possibilities; seeing yourself represented is huge.”

“This representation for “young […] Black and brown children, [who] don’t see themselves in these museums […] is really important,” says Shaumba-Yande Dibinga, founding Artistic Director of the OrigiNation Cultural Arts Center. Basquiat brought hip-hop culture, which was created by people of color, into the art world. Seeing recognition for his work will help inspire young people of color.

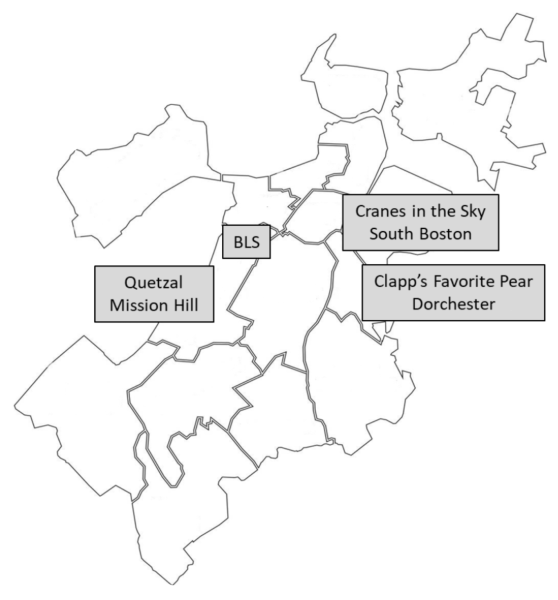

Mr. Joseph Carrigg, an art teacher at Boston Latin School, was in art school during Basquiat’s rise to fame. He says, “The feeling at our art school was [that] he came to fame too soon, and was not trained in art, but [I] think that is the point of graffiti art. The rough, crude style of it shows that these artists are just expressing themselves with the skill they have, and the passion they have for their spray painting medium and unique subject matter.”

Caitlin Donovan (III) finds “this art style more intriguing than others since [it] could be found in a museum, or on an alleyway.”

Mr. Carrigg adds, “Graffiti out on the street has an energy of revolt and resisting authority [but,] when it moves to the galleries, it becomes something else.” The transition from street art to gallery art marks the recognition of these artists, but it’s important to not lose its message in the art world, as it was originally an “explosion of energy coming directly from poor neighborhoods.”

This exhibit recognizes the incredible work of artists who were not given proper recognition during their lives, and it is one of the first to contextualize their works within the Hip-Hop generation.