Alex Fortes is a member, or Crier, of A Far Cry, a Boston-based classical music chamber ensemble. As a seasoned musician, he has played in quartets, orchestras and other ensembles around the world. A Far Cry’s esteemed accomplishments include two Grammy nominations and a Top 10 Album of the Year dubbed by National Public Radio. The Argo sat down with Fortes to hear his insights as a Crier, as well as his recently curated season-premiere performance, Then Is Now, which the group performed on September 20. Check out their official website, afarcry.org, for further information!

Q: I find the group’s conductor-less approach very interesting and unique. What are some dynamics that distinguish this group from other ensembles?

A: We have a longstanding saying that we’re not “conductorless” but “self-conducted”—it’s good marketing, but it’s also true. What distinguishes A Far Cry is that every single person takes the responsibility and ownership to “conduct” the orchestra. This might mean leading from the back with interpretive thoughts during rehearsal, or trying to spontaneously make eye contact from the back stand of the violas to the back stand of the violins during a performance.

Many observers note that, even compared to other “conductorless” groups, A Far Cry is very “parliamentary.” Our culture has evolved to value process as a way to unify 18 different musical opinions into a cohesive whole. We’re not quoting points of order in rehearsal and we don’t have an in-house parliamentarian, but sometimes we’re not so far from that either.

Q: As a curator, how did you come up with the idea, and what was the process of creating Then Is Now?

A: I’ve always been fascinated with nostalgia in music. We all have personal, generational nostalgia— for example, the music we heard at age 12 tends to follow us for life to the restaurants and get-togethers targeting our age group. But music can also evoke collective nostalgia, making almost everyone simultaneously feel wistful about past memories and the emotions tied to them.

Also, nostalgia colors our sense of the present and our outlook for the future. Sometimes the past, present, and future mix together in dreamy, surreal ways; other times, the feeling is more sober and concrete.

That blend of time and memory is what I wanted to explore in Then is Now. As I was designing the program, I had in mind Salvador Dali’s famous painting depicting melting clocks alongside strange apparitions, “The Persistence of Memory.” Similar to how the ants and trees and shoreline in that painting interact with the Camembert-like clocks, each piece on the program has a really funky interaction with time—quoting, evoking, or even distorting melodies from the past to make something really personal, modern, and emotionally powerful.

I presented that initial concept and pieces to the group, at which point the process became collaborative. During workshopping, my fellow Criers made key suggestions—for example, cutting one of the pieces to make the concert a bit shorter and punchier, and adapting it for a mainstage Jordan Hall show from its original capacity as a touring program. Having everyone in A Far Cry involved in this process was especially fitting because the pieces themselves are very much a part of A Far Cry’s “memory.” Several of the pieces have been in the group’s repertoire for nearly its entire existence.

Q: Does the group have a favorite piece or composer?

A: You’ll get at least 19 different answers from the 19 of us; probably a lot more. Personally I’d say my favorite things to play both in A Far Cry and outside of it have been by Caroline Shaw and Schubert. But the Britten Variations on a Theme by Frank Bridge that we’re playing this concert is up there as one of the best string orchestra pieces ever written, and it’s a lot of fun to play.

Q: Can you please share some memorable moments that capture A Far Cry’s personality?

A: Oh wow— well, one moment that illustrates the group’s unabashed willingness to commit to an idea and see it through to the max was a concert about 10 years ago that explored improvisation in all its aspects.

We started by improvising embellishments in a 17th-century baroque concerto grosso. We finished the first half by premiering an experimental piece that included a few of us dancing with scarves, doing sit-ups on the stage of Jordan Hall, and climbing onto a chair with a large, heavy, hardcover “History of Rock & Roll,” dropping it onto the stage to signify the end of the piece (titled “Drop the Book”).

Then we came back after intermission to play a Mozart concerto with the esteemed Mozart scholar and pianist—and one of the most inspiring improvisers in an 18th-century style—Robert Levin.

Q: Besides Then Is Now, what upcoming projects are you excited about this season?

A: I think we have a really exciting season coming up. Our Jordan Hall concerts are all amazing and quite personal, and all very different.

I’m particularly excited about our January extravaganza collaborating with Project STEP and NEC. It’s a program concept that has been simmering for nearly 20 years, where we’ll play a concert “backwards”—starting with the “encore” and ending with the “opener.”

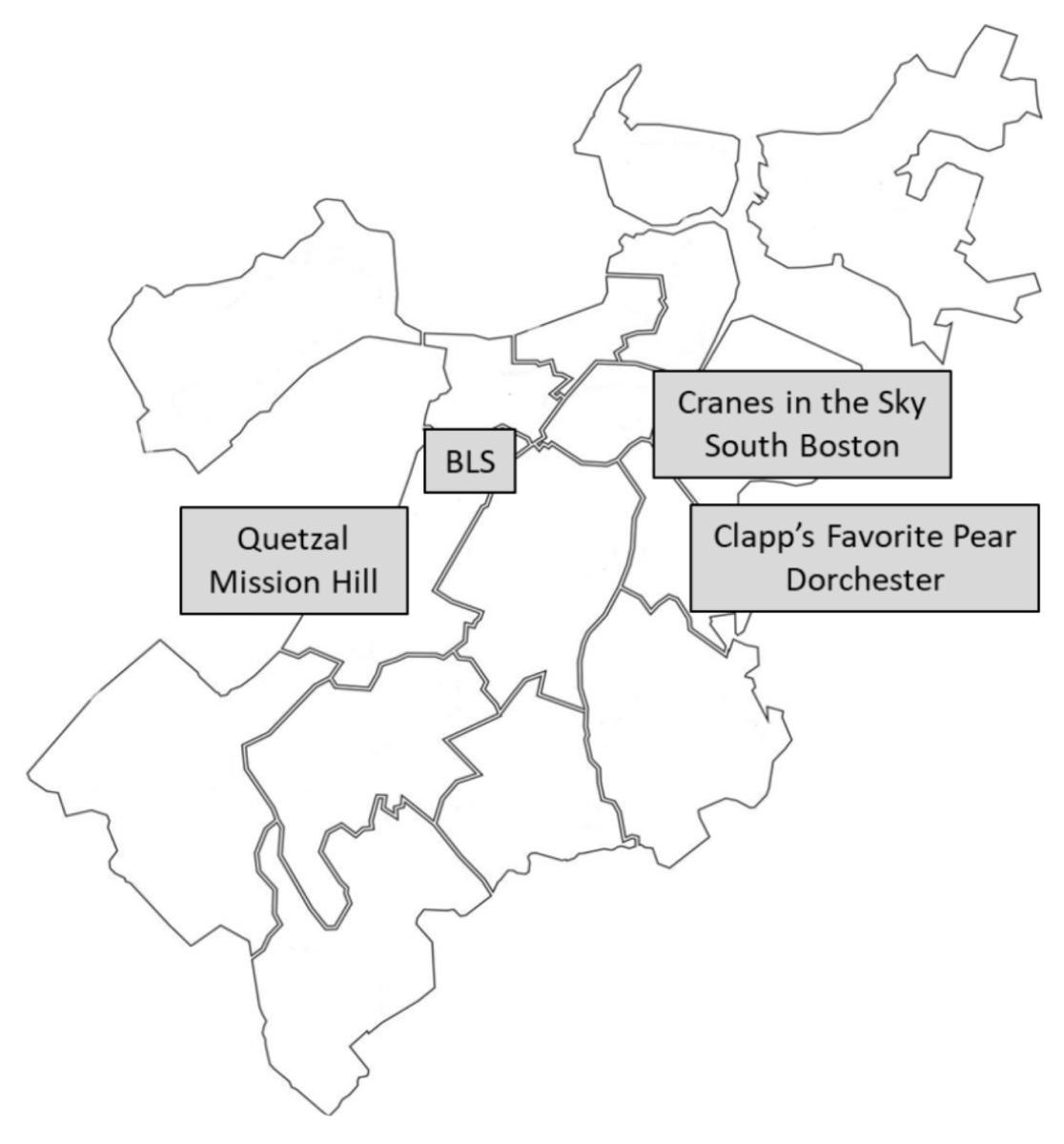

We’re also inaugurating several concepts on our chamber series. This includes a “Coming to Boston” series that focuses on the different cultures that ended up in Boston and how they changed the city, as well as how Boston changed them. Our October concert will focus on Korean immigrants. We also have our January collaboration with the multi-disciplinary musician Yeemz that takes a little further out of the “classical” box than we’ve been in a while.

Q: Many of our readers are student musicians — what is a lesson or advice you would give to high schoolers who aspire to pursue music in the future?

A: First, I’m sure lots of people say this, listen to a lot of music. Live, recorded, old, new. Any and every genre. It’s so easy now.

Also (probably also cliche) there are no straight lines. I loved music as a high schooler and it was a big part of my life, but I was afraid to make it a career because I was told it was so “hard” and “unstable.” I was also interested in a lot of other things. Studying other things led me back to music and music led me back to those other things, over and over, and continues to do so even as part of my professional music career.

In high school, I was serious about violin but I was also very interested in biology. I cold-emailed a few labs at a research institution nearby that looked interesting and got hired as a summer lab assistant by one, primarily because the head of the lab was interested that I was a violinist. He thought that would mean I was less likely to contaminate the cell cultures in his petri dishes than the average teenager.

I ended up studying not biology but social sciences in college while playing a lot of music, then went to grad school for music, and now freelance out of New York and Boston doing musical projects like A Far Cry where I get to be inspired by the music I’m playing and the colleagues I get to play it with. It also is “harder” and “less stable” than other careers that classmates have chosen, and I’ve had many of my serious musician friends make other choices and also end up happy, both more “stable” versions of a professional music career, and paths that incorporate being a serious amateur musician with a different career entirely.

That’s my own story, but if I had to generalize: try to find ways to maximize doing the things that interest you and challenge you while you are in institutions—like high school and college and music lessons and orchestra—that are designed to aid you in doing so. Of course practice, but also learn how to work with peers—that’s a key part of many jobs both in and out of the music world. And while it’s important to plan ahead, expect there to be a lot of changes in those plans as you go.