MFA Brings New LIFE to Photojournalism

We may think of history as purely informational — a set of facts cemented in books and newspapers. All the material that we have learned, however, has been carefully curated to please readers. An example of this phenomenon is photojournalism, which publications have used for centuries to create images representing the past, present and future.

“LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photography,” an exhibit currently on display at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), showcases this unique medium by exploring photo manipulation and preservation. The exhibit starts with background information about LIFE Magazine’s audience and the iconic events of the 20th century. Although it was founded as a more humor-focused publication, LIFE’s most well-known iteration as a photo-based magazine began when Henry R. Luce, the owner of TIME magazine, purchased it in 1936. It was printed weekly until 1972 and reached 25 percent of the United States population at the height of its popularity.

The exhibit focuses on the careful mapping process that went into each image’s creation. Most photographers worked directly with the magazine’s staff writers or executives to get the shot they were looking for, not necessarily the shot that best depicted the reality of the event.

Despite the fact that their subjects are live events rather than posed figures, photojournalists still behave like artists. Boston Latin School visual arts teacher Mr. Joseph Carrigg describes photography’s difference from other art forms, saying, “Painting and drawing take so long, [but] with a photo you get the lighting, different themes, angle and shot.” Photographers for the magazine still had the final call on the lighting and composition of the photograph, as long as it resembled the “story-building team’s” plan.

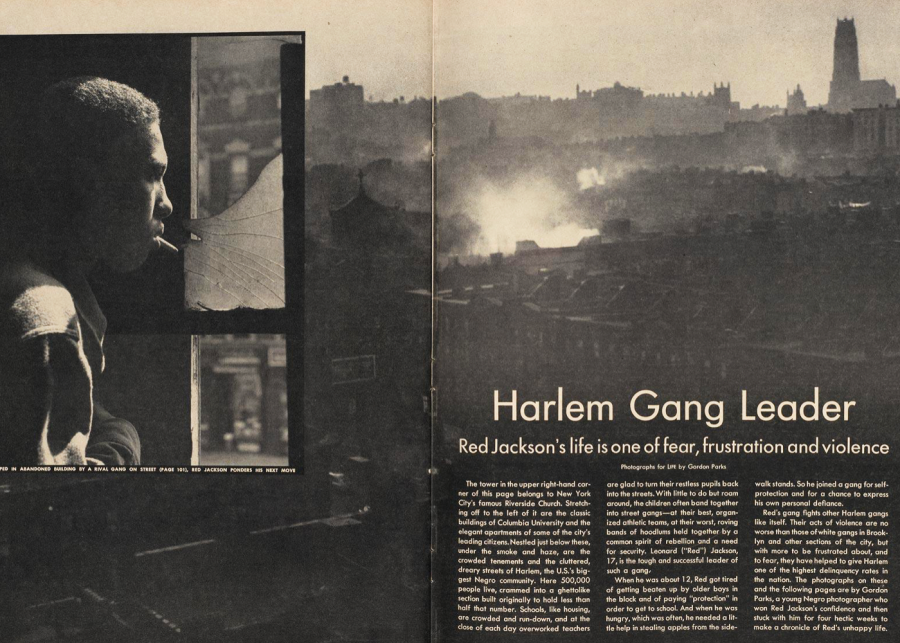

Guided by this idea of story-building, LIFE specialized in capturing moments from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. For example, photographer Gordon Park’s 1948 photo essay about Harlem gang wars and gang leader Red Jackson portrayed stereotypical moments of violence and unexpected moments of peace.

Hannah Oh (I) reflects, “Park’s portrayal of [Jackson] was moving. The photographs, by depicting him like any other normal person, effectively humanized him. The photos themselves were powerful and evocative.”

In addition to the photos taken for the magazine, the exhibit incorporated videos, as well as physical and digtal copies of LIFE. These photos include LIFE’s coverages of World War II, the Vietnam War, Neil Armstrong’s moon landing and former President John F. Kennedy’s assasination.

Even though LIFE’s iconic photos were the centerpiece of each display, the exhibit also featured works from three contemporary artists: Alfredo Jaar, Alexandra Bell and Julia Wachtel. Their artwork shone a light on the systemic racism present in photojournalism. Bell’s series of screen prints illustrated the media’s prejudice towards marginalized groups by reworking multiple covers of The New York Times newspapers. Bell used a red Sharpie and highlighter to cross out and comment on the original journalists’ diction, which suggested an inner bias towards people of color.

The exhibit further documents less well-known but equally important aspects of photojournalism, including the alteration of images and the adjustment of newspapers’ layouts. These processes have changed significantly as the technology of photography has progressed; airbrushing and cropping were both manual tasks in the 20th century.

Overall, this showcase is a must-see for anyone interested in photojournalism, and it is relevant to any American consumer. Every day, everywhere we look, we encounter images used in advertising and media, so it becomes important that we know the motives behind them.

Next time you are sitting in history class, reading your favorite magazine or scrolling through the endless stream of images online, be aware that they have been carefully curated for a specific audience.

Dante Levendis (II), the president of the digital photography club, has a similar reminder. He highlights, “It’s one thing to talk about history, but seeing images or videos or other forms of media actually portraying what is going on gives you a deeper understanding of the topic or concept.”