Netflix’s This is a Robbery Steals the Show

Have you ever seen the empty frames that hang on the walls of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston? If the answer is yes, you may know that they are a result of the massive art heist that took place on the morning of March 18, 1990. Isabella Stewart Gardner herself once wrote in her will that her art collection in the museum would not be changed over her dead body. 31 years later, however, the 13 stolen paintings from her collection remain missing with a 10 million dollar reward on the line, and Isabella’s will for the permanence of her procured artwork in Boston stays unfulfilled.

The Netflix series, This is a Robbery: The World’s Greatest Art Heist, began streaming in April and explores this robbery in a four-episode mini-series that was filmed and produced over the course of seven years. The series, directed by Colin Barnacle, is a combination of current interviews, footage from that time and scenes acted out by faceless actors. The show covers a broad spectrum of information, ranging from art history and identification of artistry styles to a comprehensive description of the inner workings behind organized crime in the Boston area.

While this wide range of topics serves to make the series diverse and exciting, it also clouds its direction. The series’ vision could be improved if each episode more clearly explored one aspect of the crime, rather than a disjointed collection of information and interviews. Boston Latin School student Elliot Strand (VI) agrees with this sentiment, stating, “[Although I] liked the show, it was way too drawn out.”

A more appreciated aspect of the show was the combination of audio and video from when the event occurred and scenes that were filmed for the documentary in which actors’ faces were not kept visible. The show is largely framed around blame and innocence, as it builds a suspenseful case for a certain person’s responsibility, and then tears down its own argument.

This happens specifically in the second episode, “Vipers in the Grass,” in which they place blame upon the guard, Richard Abath, who unroutinely buzzed the robbers into the building. They claim that he could’ve had a connection with the robbers, who were dressed as police officers. But the moment that they want you to truly believe he had some involvement, a shot pans up on the actor impersonating him smirking. His eyes, however, are still covered in duct tape, being held hostage. This moment was well-produced; it humanizes him by showing some of his impersonator’s face, while also demonizing him with a sly smirk, even though at that moment they claim him to be innocent.

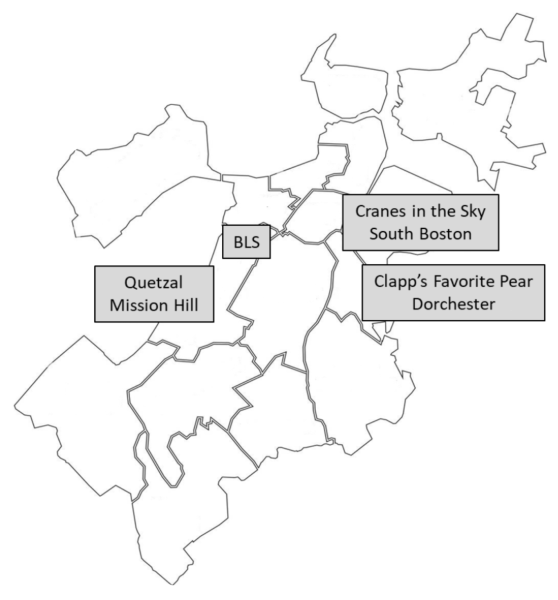

This series bears a strong connection to the BLS community, not only because of the museum’s proximity to the school but also because two eyewitnesses of the incident, featured in the series, are BLS alumni. Justin Stratman ‘90 and Nancy Clougherty (‘90) were interviewed about their eyewitness accounts. The two were walking on Palace Road and saw two people, seemingly police officers, in a parked car outside of the Museum. It seemed completely inconspicuous. Clougherty even states that she “probably wouldn’t have remembered [that] night, if it hadn’t been for what happened later.” The heist happened later, and those two “police officers” were the thieves.

Overall, although the series is drawn out and disjointed at times, it gives plenty of interesting context for a complex and unsolved case. Many timeless pieces of art were stolen, and a parallel can be drawn between this robbery and one of the stolen pieces:

Rembrandt’s 1633 A Lady and Gentleman in Black. As the title states, it de- picts a lady and her husband in black. Through X-rays, art historians found that there was once a child painted between them. It was painted over, most likely because the child died and it was too painful for the family. The loss of these 13 paintings is treated like a death in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum family, as these frames hang empty of stolen artifacts, constantly reminding us of what remains missing.